Why LLMs behave unpredictably: generalization and the invisible fill-in

Introduction - Why Does LLM-Based Software Feel Unpredictable?

In Part 1, we visited the question: “Is there something fundamentally random about LLMs?” The answer was yes and no – or as Germans say, Jein. Technically, everything is deterministic: neural networks are just math running on normal hardware. But in practice, production LLM systems introduce variance through sampling and serving-stack effects: dynamic batching, Mixture of Experts (MoE) routing, and other invisible execution details. Even with temperature=0, the same input can produce different outputs depending on the runtime context. Production systems accept this since the quality is usually not affected, and the efficiency gain is significant.

That investigation was a useful foundation to understand how LLMs work and utilize randomness. However, we still have not answered the bigger question: “Why does LLM-based software feel unpredictable?” When someone complains that their LLM-based system is “unpredictable,” they’re rarely talking about slight word choice variations from serving-stack variance. They’re talking about something more unsettling: “It worked perfectly 99 times, then completely failed on the 100th.” Or: “I asked the same question twice and got fundamentally different answers – one helpful, one useless.” What is causing this? If it’s not the non-deterministic calculations, then what is the reason?

In this post, I would like to explore this bigger source of LLM unpredictability: generalization. Every prompt you send to an LLM is underspecified – full of implicit assumptions and unstated context. The model fills in these gaps using its own understanding of the world. When its fill-in matches your expectations, the system feels magical. When it doesn’t, the system feels broken, random, unreliable. Understanding this dynamic – why it happens, what it looks like in real production systems, and what we can do about it – is the goal of this article.

The Core Insight - Generalization

Let me start with something we can easily reproduce. Open your favorite LLM – GPT, Claude, or any model – set a low temperature (e.g. 0.2-0.4), and ask it to complete this simple task. Run it a few times:

Continue the sentence: The weather was...

Here are some completions I got from GPT-4.1 at low temperature:

The weather was unusually warm for early spring, with sunlight streaming through the windows and a gentle breeze carrying the scent of blooming flowers.

The weather was unusually warm for early spring, with a gentle breeze carrying the scent of blooming flowers through the air.

The weather was surprisingly warm for early spring, with a gentle breeze rustling through the blossoming trees.

The weather was unexpectedly warm for early spring, with sunlight streaming through the windows and a gentle breeze rustling the new leaves outside.

...unusually warm for early spring, with sunlight streaming through the windows and a gentle breeze rustling the curtains.

The weather was cool and breezy, perfect for an afternoon walk in the park.

Look carefully. What’s strange here?

First: why spring so often? The prompt doesn’t have anything about season or time. Second: why the formatting differences? One response starts with “…” (just the continuation), while others output full sentences. Third: notice the variation isn’t just stylistic. The model is making different choices about what the prompt means.

Here’s the thing: when I wrote this prompt, I was vaguely expecting traditional language model behavior – pure next-word prediction, like the wheel-of-fortune sampling we discussed in Part 1. I expected something more neutral, more “textbook language completion example.” But that’s not what I got. And the reason is simple: I underspecified my request.

To get what I actually intended – traditional language-model-style completion – I would have needed to write something like:

Act as a pure language model performing next-word prediction with no contextual assumptions. We have no context at all - no 'now,' no 'where,' no assumed situation. Complete the following sentence fragment into one full sentence, including the given words. Keep it neutral on topics, behave as if you have sampled out of all possible sentences that start with the given sentence parts. Sentence: "The weather was..."

That’s quite some amount of specification for what seemed like a trivial task! And this reveals something fundamental: it is (always) underspecified. “Continue the sentence” seems simple. But it contains hidden assumptions that must be filled in:

- Goal – what output would make a ‘success’? A sentence that matches “here and now”?

- Context – what is “here” and “now”? What season? What situation? Or none at all?

- Format – write only new words? Repeat the original and complete it?

- Style – natural extension? Surprising twist? Neutral completion?

GPT-4.1 filled them in with “generate a sentence that is likely to be observed here and now”, and then filled in “now” as best as it believes.1 The human asking and the LLM answering must be in sync on all these implicit dimensions. But we rarely are – and neither party sees the mismatch until the output appears.

So how does the LLM handle this underspecification? It generalizes. The model fills in missing information using its own understanding of the world. “Continue the sentence” becomes “write something appropriate for here and now that starts with the given partial sentence.” Spring feels right. Evocative language feels natural. The model isn’t wrong – it’s doing exactly what it was trained to do: produce helpful, contextually appropriate responses. This is the core capability that makes LLMs useful. Without generalization, every prompt would need to exhaustively specify every dimension (as in traditional programming). The whole point of LLMs is that they understand what you probably mean, even when you don’t spell it out.

But here’s the problem: the fill-in is invisible. You don’t see the model decide “it must be springtime” or “I should write the full sentence.” You only see the output. When it matches your expectations, the system feels magical – it just understood. When it doesn’t match, the system feels random and unpredictable. Moreover, the non-determinism in production LLMs we visited in Part 1 can also affect which generalization “wins”, so even the same prompt can trigger different invisible fill-ins. In the example above, most of the calls decided “full sentence format”, but one of them selected “just the new words”. We don’t see this fill-in process, hence “invisible”. We only see the different outputs and wonder why.

This is what researchers mean when they talk about the shift from traditional to AI programming. Omar Khattab2 put this well in a post on X:

The change is that it’s inherently underspecified, fuzzy, and relies entirely on generalization – which is opaque and extensive… … and that means that you cannot easily reason about how two different ‘similar’ inputs would behave.

The challenge isn’t randomness. It’s that we cannot see what the model is filling in – until it fills in something we didn’t expect. In my production experience, the dominant source of “unpredictable” behavior is generalization under underspecified inputs; sampling and serving-stack variance exist, but they are secondary to interpretation shifts. Other contributors exist – retrieval misses, tool failures, safety overreach, and long-context loss – but they tend to feel like discrete errors rather than the chronic “it’s unpredictable” itch.

Generalization Failures in Production

The minimal example above is interesting in the sense that it shows clearly what the LLM is filling in and the process of generalization. But that example is harmless – who cares if the weather sentence mentions spring or has a bad format? In production systems, the same mechanism causes real problems. I’d like to share some memorable cases. Each illustrates a different flavor of generalization failure. For each one: what happened, why it happened, and what fixed it.

Case 1: Assuming the context of a query from the context of search results. The Biomedical Fixation

One of the first tools we shipped was an LLM-based search re-ranking module – think of it as a layer on top of search results. Traditional search returns the top 20 candidate snippets; then an LLM reads them and selects the best 3 for the user to see. Fast, effective, and it matched human judgment remarkably well. It had been running smoothly in production for months, serving many customers. Then we deployed it on a German university’s FAQ system, and something strange happened. A student asks: “Wann ist der Bewerbungstermin?” – “When is the application deadline?” A completely general question about university admissions. The search results included general knowledge base entries like “What deadlines do I need to observe for applications?” right at the top. Easy case, right? But GPT-3.5 consistently selected the biomedical-specific entries instead. Not occasionally – consistently. Entries like “When can I apply for the Applied Biomedical Engineering program?” kept winning over the obviously correct general answers. Even GPT-4 era models failed when the model size was small. GPT-4o-mini still failed 20-30% of the time – and the failures seemed random. Later models (such as GPT-4.1) never made this mistake.

What was the invisible fill-in? The candidate pool happened to contain multiple entries mentioning “Biomedizin” – the university has several biomedical programs. Among 20 search results, entries related to biomedical departments appeared 5 or 6 times. The model saw this distribution and filled in: “This must be a biomedical-focused institution.” It then reinterpreted the general query as: “When is the application deadline [of this institution = biomedical research academy]?” And then it correctly answered the wrong question.

What fixed it? One option was to inject context: “This is a full university with many departments, not a specialized biomedical institution.” That works for this case – but it doesn’t scale. A generic re-ranking module can’t anticipate what false inferences might arise from every possible candidate distribution. Next deployment might trigger “this is a travel agency” or “this is an IT company.” The real fix was simpler: use a model with better generalization. Say, GPT-4.1 and later models, even the minimal “nano” size model, didn’t make this unjustified inference. They understood that the distribution of topics in search results doesn’t define the nature of the query. It seems obvious in hindsight – you shouldn’t assume the context of a query based on the contents of search results. But smaller and earlier models failed on this for quite some time. The capability gap was invisible until we stepped on it.3

Case 2: The Invented Commands

One of our LLM-based customer service systems used special command strings to create interactive elements. When the knowledge base entry provided to the LLM contains something like {COMMAND USE FORM 1234}, the LLM is supposed to copy this string exactly into its response. A downstream parser then detects the pattern and renders it as a clickable button, interactive content, or web form, and so on. The instruction seemed clear: “If the source text contains a command string, copy it exactly into your response.” But occasionally, roughly 1 in 100, the LLM would write something like {COMMAND USE FORM “Angebot anfordern”} – using the semantic meaning (“request a quote”) instead of the database ID. Even worse, sometimes it invented new commands like {COMMAND USE FORM “contact form”} when it is confident there is a contact form somewhere (e.g. contact forms were mentioned in the knowledge base, but without link or command for that). This happened across model generations. Even mature models like GPT-4.1 occasionally invented commands – rarely, maybe one in a thousand, but reproducibly.

What was the invisible fill-in? The LLM read our instructions: “This string becomes a clickable button in the next processing step.” And it filled in: “The downstream system must be intelligent. It will understand what I mean.” (!!) So it “helped” by writing what a smart colleague would understand. “Activate the quote request form” is clearer than a mysterious ID number, right? But the reality is that our parser is purely mechanical. It does simple 1:1 string matching. It can only process exact patterns with valid database IDs. Anything else causes a silent failure – the button simply doesn’t render.

What fixed it? We tried explicit prohibition: “Don’t make up commands! Copy them exactly as written with those IDs!” It helped, and greatly reduced these made-up outputs, and we believed that this was solved. But no, the problem still reappeared occasionally. The negative instruction didn’t fix the underlying wrong belief. It just tried to be “more careful” about not inventing things, but it sometimes failed. What finally fixed it was describing the reality:

"The downstream application has no intelligence. It performs simple 1:1 string mapping. If the command string does not exactly match what was observed in the source - character for character - it will cause an error and the button will not render."

This worked. By correcting the model’s assumption about how the world works, the behavior changed. The lesson: don’t just forbid the behavior – explain the world correctly. Negative instructions fail when the model still has a wrong belief about why the forbidden behavior would be okay. Correct the belief, and the behavior follows.

A Better Mental Model: Floor Grating

Andrej Karpathy coined the term “jagged intelligence” to describe a fundamental characteristic of LLMs: they can solve complex problems that impress us, while simultaneously failing at tasks that seem trivially simple. A visualization he shared captures this well – and adds an important nuance: human intelligence is also jagged, just in a different shape.

Human intelligence (blue) and AI intelligence (red). Both are jagged, but in different directions. (Source: Karpathy’s 2025 Year in Review)

Human intelligence (blue) and AI intelligence (red). Both are jagged, but in different directions. (Source: Karpathy’s 2025 Year in Review)

The classic example: an LLM can write sophisticated code, analyze legal documents, or explain quantum physics. But ask it to count the number of ‘r’s in “strawberry” and it fails. The capability landscape is jagged, not smooth. Unlike humans, where abilities tend to correlate and develop together from birth to adulthood, LLM capabilities are scattered – peaks of surprising competence next to valleys of surprising failure.

This framing is useful. It warns us: don’t assume that because an LLM handles complex task X, it will handle simpler task Y. The landscape is uneven. Check your assumptions. But I think “jagged” captures only part of the story. The jagged framing suggests: there are areas the LLM covers well, and areas it doesn’t cover. If you’re in a covered area, you’re fine. If you wander into an uncovered area, expect problems. My experience in production suggests something different: even the “covered” areas aren’t solid ground.

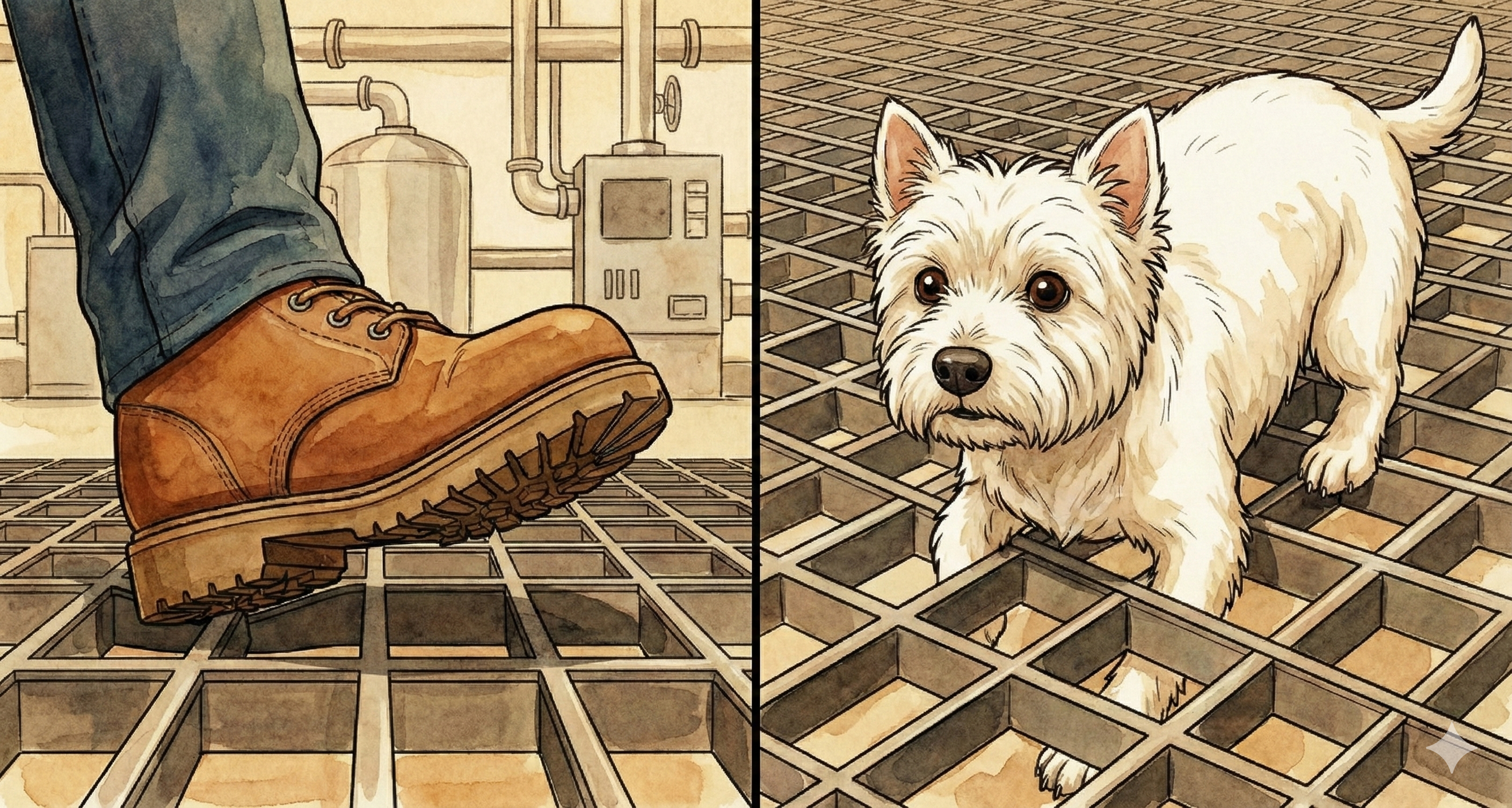

Let me offer a different mental model: floor grating. Imagine an industrial floor made of metal grating – the kind you see in factories, on catwalks, in mechanical rooms. From a distance, it looks like a solid surface. Walk across it normally, and it feels solid. Your foot lands, the grating holds, no problem. Now imagine a small dog trying to cross the same surface. Its paws are shaped differently. They slip through the gaps. What felt like solid ground to you is an obstacle course for the dog.

The biomedical fixation case is a perfect example. Search re-ranking felt like “covered ground”. We’d tested it extensively, deployed it across many customers, watched it perform well for months. It looked solid. Then we brought a problem with the wrong shape: a general query against a candidate pool with skewed topic distribution. The model’s assumption (“we can infer context from search results”) was a gap in the grating we’d never noticed. Our previous problems had been shaped like human feet. This one was shaped like a dog’s paw. And here’s the key difference from “jagged intelligence”: we were still in the capability area. The model could do search re-ranking. It wasn’t a case of asking it to count letters or do something outside its competence. It was a subtle gap within a capability it demonstrably had.

Better models have tighter grating – fewer gaps, smaller holes. For example, the latest models handle search result reranking just fine, even on those edge cases previous models often failed. It now feels really solid. But maybe it is just tighter than before. Occasionally, a problem with an unusual shape still catches on a gap, one stumble among many smooth steps. This is why some LLM toolkits recommend practitioners to “always assume there will be edge cases when you go to production.” I fully agree: the grating analogy is my preferred way of explaining this. The software (LLM and the configured system as a whole) now looks solid – the grating seems to be tight enough – but please be aware it is still grating; some will still get stuck.

The unsettling implication: you don’t know where the gaps are until you step on them. Your test suite might have problems shaped like human feet. Production traffic brings dogs, cats, high heels, and shapes you’ve never seen.

More Patterns from Production

With the floor grating model in mind, let’s look at two more cases. These show subtler failure modes.

Case 3: “… I think it is dangerous to trust ski shop opening times”

We deploy AI-powered customer service across many different businesses – retail shops, restaurants, medical offices, service providers. One of the most common tasks: answering questions about opening hours. “When are you open?” or “Are you open at (specific time)?” This is a simple task: look up the hours from the knowledge base and respond. It works correctly thousands of times across hundreds of deployments.

Then we noticed something strange with a ski shop. The LLM would output the correct opening hours – exactly as stored in the knowledge base – but then add an unsolicited caveat: “However, I recommend contacting them directly to confirm, as hours may vary depending on conditions.” Nothing in the knowledge base suggested this. No instruction told it to add caveats. The provided hours were accurate and complete. And this only happened for ski shops. Not for restaurants. Not for retail stores. Not for medical offices. Just ski shops.

What was the invisible fill-in? We suspected that the model had learned something from its training data: ski shops are weather-dependent businesses. Snow conditions affect operations. Hours might be unreliable. So it somehow assumed: “The opening hours for this type of business may not be trustworthy. It is better to be safe, isn’t it?” This was not a case of missing information. The model had the correct hours. It just didn’t trust them, because its training prior about ski shops overrode our instruction to report the knowledge base content faithfully.

What fixed it? One way that worked was adding a meta-confirmation: “The opening hours listed are accurate. The shop operates consistently throughout the season regardless of weather conditions.” 4 This explicitly told the model: don’t apply your general beliefs about ski shops. The caveat disappeared.

The lesson: Sometimes the problem isn’t that the model lacks information – it’s that the model is adding information you don’t want. The ski shop case wasn’t about underspecification in the prompt. The instruction (“be truthful to the knowledge base”) was followed, and the hours were correct. But the model filled in something extra: “For this type of business, a helpful response should include a safety warning.” This is a different shape of generalization failure. The model wasn’t filling in missing context from the prompt. It was filling in additional context from its own beliefs about the world, deciding that being truly helpful required more than just the facts we provided.

To fix it, we had to explicitly tell it what not to add. Not because it disobeyed our instruction, but because it went beyond it in a way we didn’t want.

Case 4: Emergent Geography – Sometimes

Modern LLMs are surprisingly good at geographic reasoning. They know where cities are and can estimate which of two locations is closer to a third. This isn’t explicitly programmed. It emerges from training on text that mentions places, distances, and spatial relationships.

We first noticed this around the GPT-4 era. A test case asked a retail chatbot: “Which of your stores is closer to me? I live in Charlottenburg.” The knowledge base had two Berlin stores: Spandau and Mitte. GPT-4 would deflect:

We have two stores in Berlin. One is located in Spandau at Breite Straße xx, and the other in Mitte at Hackescher Markt yy. Both are accessible by public transport...

Then GPT-4-Turbo arrived, and suddenly:

The store in Mitte at Hackescher Markt is closer to Charlottenburg than the store in Spandau.

An emergent capability. We were excited – it felt like the model was doing something useful beyond the knowledge base. The occasional safe fallback seemed fine. But this became a real issue when we deployed for a car company in the UK. A customer asks: “Where is my nearest dealer? I live in Reading.”

Sometimes: Your nearest dealer is [Name] in [Location], approximately [X] miles from Reading...

Other times, for essentially the same meaning question: You can find your nearest dealer using our dealer search page: [link]

The same person asking minutes apart would get different responses.5

What was happening? In real usage, nobody asks the exact same question twice – small wording shifts are the norm. When a model is near a borderline decision (“answer directly” vs “deflect”), those tiny differences are enough to flip the outcome. And even when the inputs are identical, serving variance we discussed in Part 1 can still move the model across the line. This is especially true for emergent capabilities like geography, which are not engineered and have no reliability guarantees.

The floor grating is vibrating. The same foot can catch in a gap one moment and walk smoothly the next. The customer wanted consistent answers using the geographic capability. But we couldn’t provide it, since it was emergent, not engineered. The possible options were: build a proper dealer-search integration (development cost), or accept the inconsistency.

The lesson: Emergent abilities are especially brittle because the model is auto-filling invisible context – here, its own geographic knowledge with degrading accuracy and confidence as you zoom in. That auto-fill is opaque to us, so we can’t easily predict how two similar inputs will behave. Small differences in phrasing or context can push the model across a response boundary.

Why Can’t We Debug This?

At this point, a reasonable engineer might ask: “Okay, so LLMs make invisible assumptions. When they assume wrong, we get bad output. Why can’t we just… trace the execution and fix it?”

This is, after all, how we’ve solved software problems for decades. Something goes wrong. You examine the logs. You step through the code. You find the line where the behavior diverges from expectation. You fix that line. You ship the patch. Problem solved.

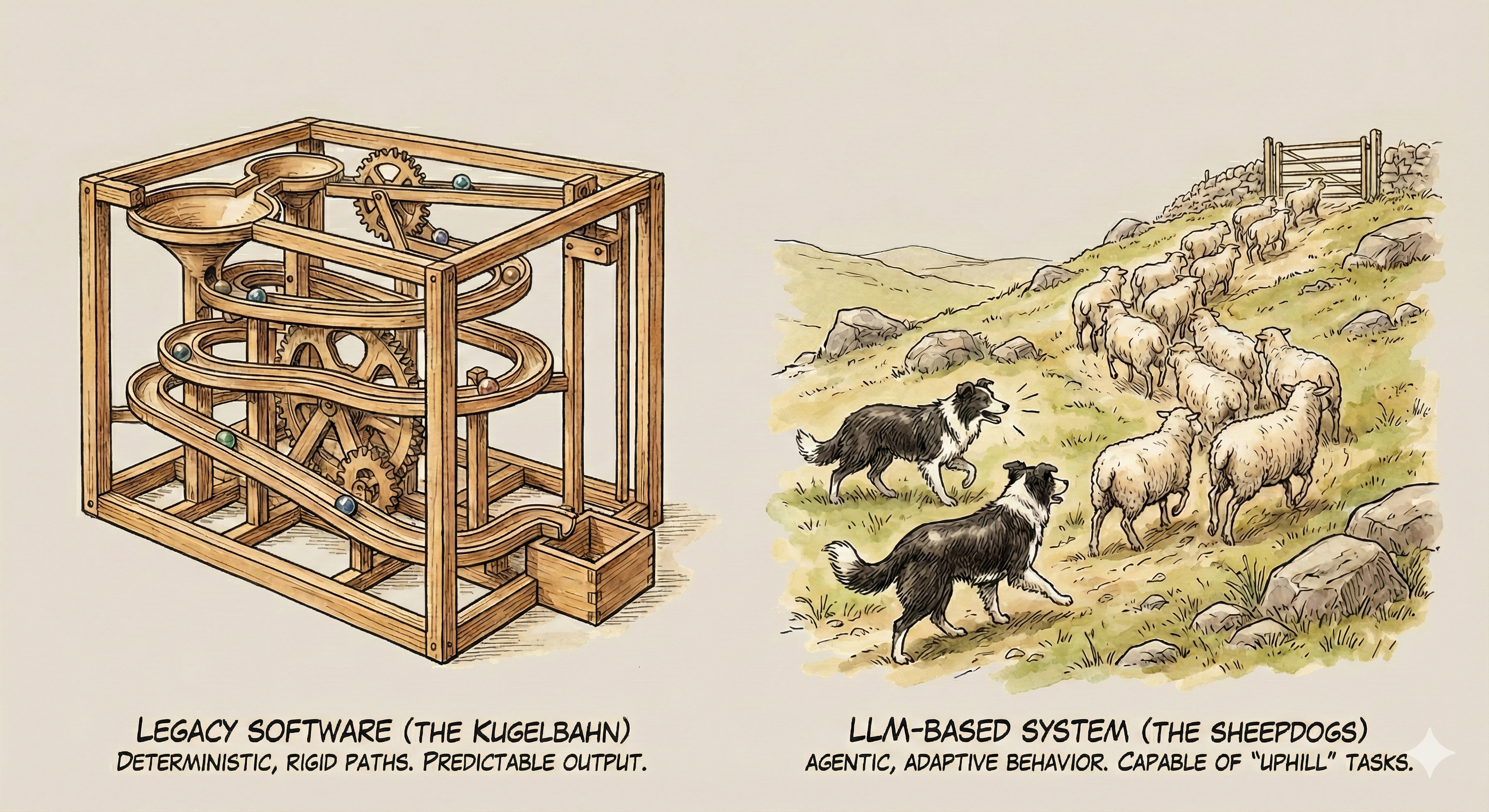

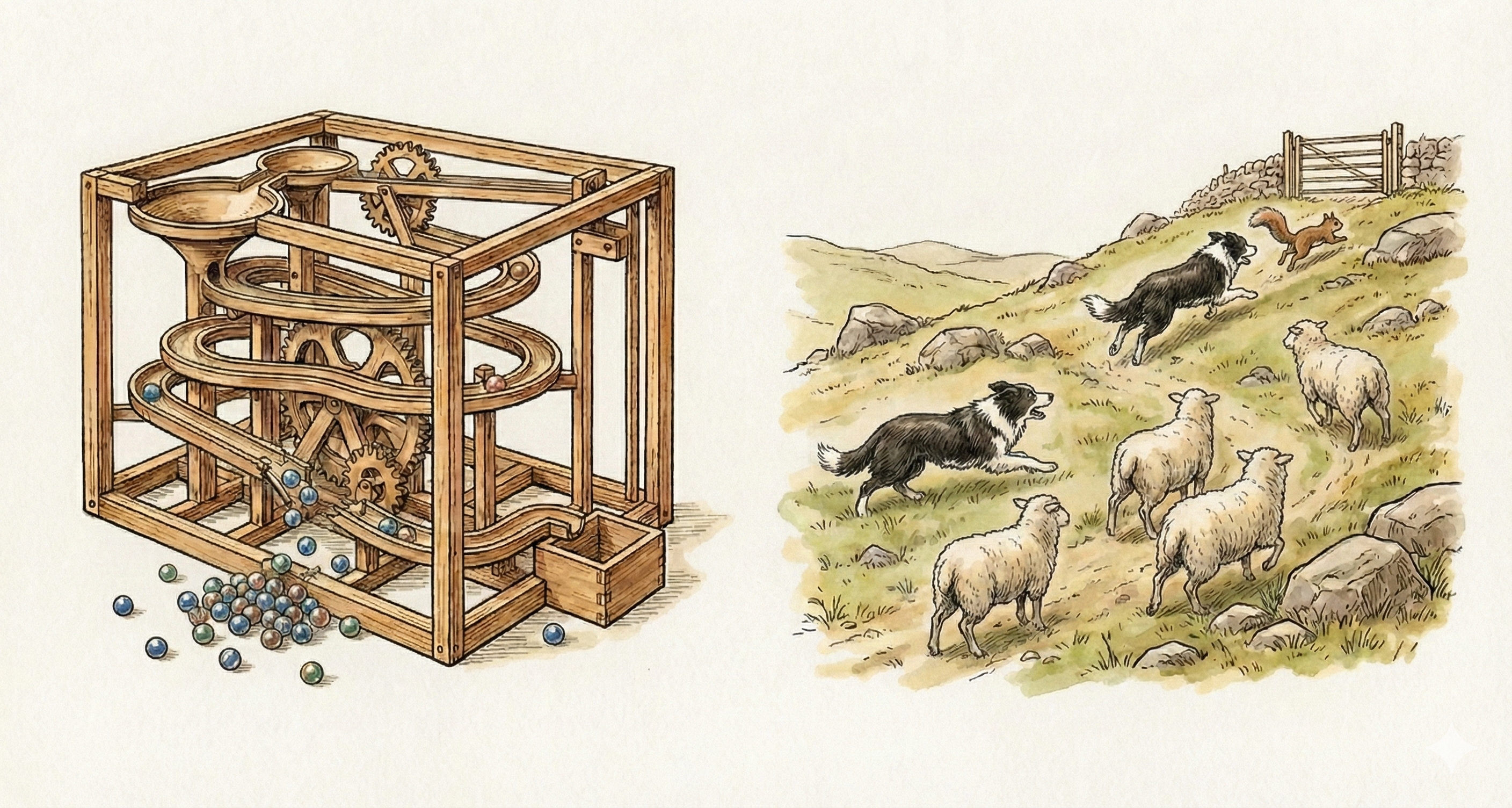

In Part 1, I compared traditional software to a Kugelbahn – a marble run. The ball rolls down the track, following a deterministic path. If it flies off at some point, you find the bent rail, straighten it, and the ball runs true again. Clear cause, clear location, clear fix.

LLM-based software doesn’t work this way. Everything is still technically visible. You can inspect every weight in the neural network, every activation value, every attention pattern. It’s all just numbers – billions of them, fully accessible. Nothing is hidden. But nothing is meaningful at human scale.

There’s no “line 347 where the model decided this must be a biomedical university.” No neuron labeled “assume downstream systems are intelligent.” No attention head you can adjust to make it stop worrying about ski shop weather conditions. The computation that leads to “add a caveat about ski shop hours” is distributed across millions of parameters, emerging from patterns learned across billions of training examples. You can’t point to it or isolate it. You can’t “patch” it.

In Part 1, I also introduced the sheepdog analogy. LLM-based systems are like coordinated sheepdogs – far more capable than marble runs. They can go uphill. They can make decisions. They can handle situations they’ve never seen before. They have something like judgment. But when a sheepdog suddenly chases a squirrel instead of herding sheep, you can’t fix it the way you’d fix a bent rail. The dog made a judgment call based on its training, its instincts, and the specific situation. To prevent it happening again, you don’t repair a mechanism – you adjust the conditions, the training, and the constraints.

This is the mental shift required for working with LLMs. We can’t trace and patch. We can’t find the bug and fix it. Instead, we have to:

- Understand the failure mode: What did the model assume? What was the invisible fill-in?

- Adjust inputs and context: Provide the information the model was missing, or tell it what not to assume

- Build guardrails: Accept that some failures will happen, and design systems that catch or mitigate them

- Choose better models: Sometimes the only fix is a model with tighter grating

This is a different kind of engineering. Less like fixing machines, more like training animals, or perhaps, onboarding colleagues from very different backgrounds. The generalization framing helps here. Once you understand that the model is filling in invisible gaps, you know where to look: what did you provide, what did the model read, and where did they diverge?

Mitigation Strategies

We can’t remove generalization. It’s what makes LLMs useful in the first place – the ability to handle underspecified requests by filling in reasonable assumptions. Remove that, and you’re back to traditional programming where every edge case must be explicitly handled. But we can work with it. We can reduce unwanted fill-ins, catch failures before they reach users, and build systems that degrade gracefully when things go wrong.

Manual Prompt Engineering

The most direct approach: add explicit context to prevent wrong inferences. We saw this in the cases above. “This is a full university, not a biomedical institution.” “The downstream parser has no intelligence – copy strings exactly.” “The opening hours are accurate regardless of weather conditions.”

This works, and it’s often the first thing to try – but it’s reactive. You discover a failure mode, then patch it. It’s also fragile: prompts tuned for one model may behave differently on another, since each model has different grating patterns. Even minor version updates or server configuration changes can affect results. And it doesn’t scale well across many deployments in different domains. Manual prompt engineering is the starting point, not the destination.

Automated Instruction Optimization

What if we treated prompt engineering like machine learning? Instead of hand-crafting instructions, we optimize them systematically against a dataset of examples. This is the idea behind tools like DSPy and similar frameworks. You define your task, provide examples of correct behavior, and let the system find instructions that work. The process looks like this:

- Collect examples of inputs and desired outputs

- Start with a basic prompt

- Run it against your examples, measure failures

- Automatically adjust the prompt (or the pipeline structure)

- Repeat until performance meets your threshold

The benefits are significant. It’s systematic – you’re not guessing what might help. It’s reproducible – run it again when you switch models. It’s measurable – you know exactly how well your prompts perform against your test set. The main limitation: you need an evaluation dataset that covers your actual failure modes. If your test set doesn’t include “general query against domain-skewed search results,” you won’t catch the search reranking issue that I mentioned earlier. The optimization is only as good as your examples. But in practice, this isn’t a major obstacle. As you deploy and gather production experience, you collect both successes and failures naturally. Once you have that problem collected on your data, this approach dramatically outperforms manual tuning.

Reflection Techniques

Another approach: let LLMs check their own work. Basic self-reflection is straightforward – after generating a response, ask the model to review it. “Does this follow the instructions? Does it make unwarranted assumptions?” The model often catches its own mistakes.

More effective is cross-model reflection: have a different model do the review. GPT writes, Claude reviews. Or vice versa. Different models have different grating patterns, e.g. gaps in different places. A mistake that slips past one model’s self-review might be obvious to another. Think of it as layering two gratings: each has gaps, but the gaps don’t align perfectly. Problems that fall through one get caught by the other. The cost is of course latency and API calls, since we need to run two models instead of one. But for outputs where reliability matters, this trade-off often makes sense.

Defensive Engineering

No matter how good your prompts, how capable your models, or how thorough your testing, some failures will reach production. A test suite with hundreds of cases still can’t cover every problem shape that real users will bring. The long tail is real. At some point, you accept this and build defenses. Graceful degradation: when something goes wrong, the system shouldn’t break. If a response fails validation, render a safe fallback instead of crashing. If a generated link is malformed, show helpful text instead of a broken button. Slightly degraded output is acceptable; a broken system is not. Monitoring: rare failures won’t appear in testing. By definition, they’re rare. Production monitoring that tracks unusual outputs, logs anomalies, and alerts on patterns is essential. You need visibility into what’s actually happening at scale. Fallback paths: design alternatives for when the primary approach fails. Maybe the fallback is less impressive – a generic response instead of a personalized one, a link to a search page instead of a direct answer – but reliability often matters more than elegance. The mindset shift: the goal isn’t zero failures. It’s zero catastrophic failures. A missing button is annoying. A crashed checkout flow loses customers. Know which failures matter most, and defend those paths hardest.

Better Models and Externalized Reasoning

Newer models do help. The search reranking problem that plagued GPT-3.5/GPT-4 doesn’t occur with GPT-4.1. The geographic inconsistency still occurs in 2025, but newer models are better calibrated in their confidence, and they fall back more consistently when uncertain, which feels less erratic to users.

Another significant shift is how we use LLMs. Traditional LLM usage is a single transaction: input -> output. The model has to do its best as if this is the last and only communication. All the fill-ins happen invisibly, and you only see the final result. Agentic approaches change this: The work mode is no longer just input-output. The model externalizes its thinking in reasoning tokens, in memos, in todo lists, in explicit plans. It shows intermediate steps to the user. It asks for opinions at decision points. It exposes the “supports” for its decisions.

Consider the ski shop case in an agentic context:

User: "When are you open?"

Agent thinking:

- Found opening hours: 9am-6pm daily

- This is a ski shop. Weather might affect operations.

Maybe not safe to trust this? Should I caveat?

- Potentially helpful tools: ski area webcams,real-time weather,

weather forecast.

- Decision: ask user rather than assume.

Agent response to user: "We're open 9am to 6pm daily.

Do you want to check if the current slope conditions are normal?"

The same reasoning process that caused the unsolicited caveat is now visible. The user can correct it: “No, just give me the hours.” Or confirm: “Yes, please check conditions.” The invisible fill-in is more exposed and becomes a decision point.

This is, I think, real progress in addressing unpredictability: making the invisible fill-ins more visible, externalizing them and making them communicable. Of course, not every use case can support this kind of iterative interaction, or even exposure of all internal thinking. But where it’s possible, it directly addresses the core problem: you can see what the model is filling in, and has a chance to correct it when needed.

Conclusion - What Did I Assume It Would Know?

Here’s a useful way to think about all of this: imagine hiring a brilliant new colleague from a completely different country and culture. She is smart, capable, and speaks all the languages of the world, and is eager to help. But she doesn’t know your team’s history, your company’s unwritten rules, or the implicit assumptions everyone else takes for granted. And alas, she is good at only one communication mode – the written communication! And more often than not, many aspects of the normal operation of your company are yet to be written down… When you ask her to do something (again, in written communication), she fills in the gaps with her own understanding. Sometimes she gets it exactly right. Sometimes she does something unexpected – not wrong from their perspective, but not what you intended.

You don’t fix this by blaming her for not knowing, or by blaming yourself for not specifying everything. You fix it by recognizing the gap and working to bridge it. You provide context. You make implicit things explicit. You learn what she’s likely to misunderstand, and you address it proactively. Over time, as you work together, the gap shrinks.

This is where we are with LLMs. The problem isn’t that the model is stupid. The problem isn’t that users and developers write bad prompts. It’s a genuine gap between two different world-models – what you assume, and what the model assumes. Neither side sees the gap clearly until something goes wrong.

For users, the practical shift is: provide context like you’re working with a smart colleague who doesn’t share your background. For developers and providers: bridge this gap proactively – extract implicit knowledge into explicit context, build systems that expose uncertainty, and where possible, use agentic workflows that make the fill-ins visible and correctable.

This concludes a two-part series

In Part 1, we asked whether LLMs have fundamental randomness – the answer was Jein. Technical non-determinism exists, but it’s manageable and rarely the real source of frustration. Here in Part 2, we explored the bigger culprit: generalization, and the invisible fill-ins that happen every time an LLM receives a prompt.

The next time an LLM does something unexpected, before asking “Why is it so dumb?” – try asking: “What did I assume it would know?”

It’s a better question. And increasingly, the AI is learning to ask it too.

-

It seems that models have different default “what is the current season” priors when temporal information is missing. In my tests, GPT-4.1 leaned “spring” (and flipped to “autumn” when the location was given as Sydney), while GPT-5.2 leaned “winter” (“summer” with Sydney). This suggests model-specific, cutoff-anchored temporal priors. ↩

-

Omar Khattab is the creator of DSPy and ColBERT. ↩

-

The reranking task was actually a harsh one for models, especially the task did not allow any thinking tokens. To optimize cost and process speed (e.g. < .5 second), LLM output was limited to a few tokens, direct list of index numbers only. LLMs didn’t have much token space to reason through the problem – they had to make quick judgments. This amplified the tendency to over-infer from surface patterns. ↩

-

Thankfully, this was actually true for this customer whose shops were located over 2000m ski area, opening all the time throughout the season. Not all ski shops were this lucky, such as German ones in the 2025/2026 season, closed longer than usual due to lack of snow… ↩

-

LLM geographic knowledge degrades as you zoom in. Models are fairly accurate at the city level, less accurate at the neighborhood level, and unreliable at street level. For example: “Heidelberg” -> accurate. “Heidelberg Ziegelhausen” -> okay. “Oberer Rainweg” (a street) -> shaky. Since dealership data is stored as street addresses, the model must reason about which of two addresses is closer – a much harder problem than comparing cities. ↩