Do LLMs have fundamental randomness? No, but yes.

Introduction

Since shipping our first LLM pipeline to production in 2023, I’ve heard the same question in countless variations: LLM-based software seems to behave rather differently, and feels like there is a certain inherent randomness in it. This is actually a reflection of my colleagues hearing the same question multiple times from our end users and customers. We hear questions like “Why does it decide differently even with the same input?”, or “Why does it work 99% of the time, but still sometimes fails?” – the underlying question is always the same: are LLM-based systems fundamentally different?

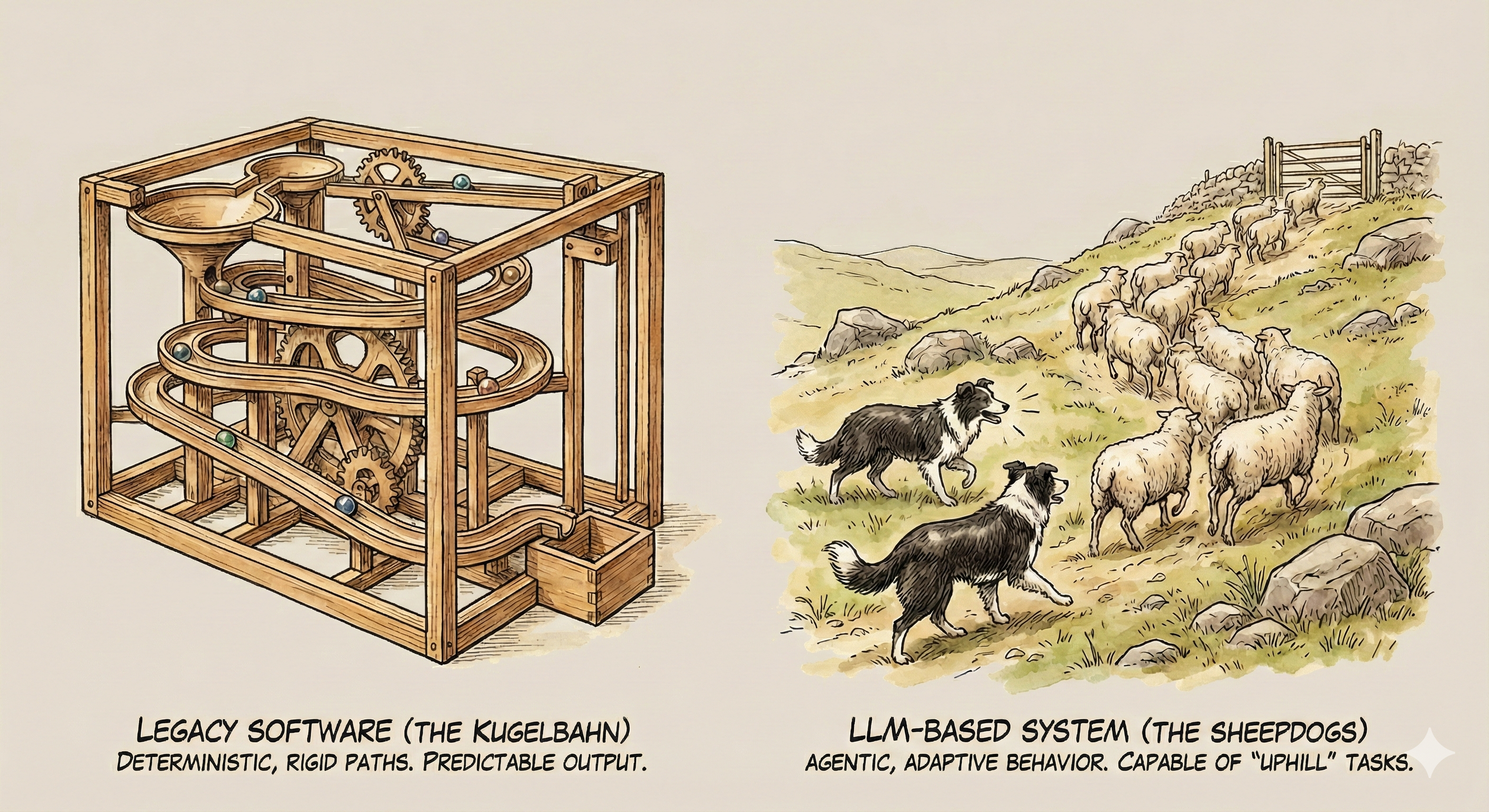

For this particular type of question, I came up with a small analogy to compare LLM-based software vs. legacy software. Legacy software behaves like “Kugelbahn” (German word for a marble run, or rolling ball sculpture). It works like a well-tuned machine, often performing an amazingly complex job. If something goes wrong, that tends to go wrong at a localized part (say, a rail has been bent), and once you “fix” that part, it tends to work steadily. However, LLM-based software, by contrast, is more like a pair of sheepdogs performing tasks together. They are much more powerful, and can perform things that mere balls cannot – such as going uphill instead of just going downwards. They even have agency and decide on their own in new situations. But just like real-world dogs, if things go haywire, the failures are generally far more creative – and do crazy stuff that we might not have predicted. When they misbehave, instead of “fixing” it, you put leashes on them, or set bounds with guardrails, to guide them and keep them under control.

I find this analogy works well for my colleagues, especially as it naturally leads us into concepts like leashes and guardrails, which is a different “mode” of interacting with software to improve results. However, it also opens a more technical question that is tricky (i.e., it needs more space) to answer. The analogy is actually leading us to: “there is something fundamentally different about LLMs, that it is more lively, and inherently random and unpredictable.” This is a hard question to answer briefly and accurately. The answer is “No, but also Yes” – and understanding why requires digging into how LLMs actually work.

It is an interesting topic, and may help us understand better how LLM-based software works with us. So I decided to write a two-part article about this. In this post, I will first explore the technical sources of randomness in LLM processing – if we run “the same input” 100 times, do we always get the same result? If not, why not? And in Part 2, I will visit bigger and broader issues around LLMs: that you cannot easily reason about how two “different but similar inputs” would behave. Your customer support LLM pipeline might work perfectly 99 times when passing along the opening hours of a ski shop, then mysteriously suggest that you cannot trust the written opening time, and the customers should always try to call the shop to make sure on the 100th. Why does it do so? And how can we mitigate that?

Randomness and Neural Networks

Neural networks, including LLMs, run on “normal” computer hardware: they might run on exotic pieces such as GPUs, TPUs, NPUs or whatever chips are marketed for running NNs quickly. But all those systems are still normal computational hardware, and the math itself is deterministic: given the same inputs and the same numerical path, you get the same outputs. There is no inherent magic or dice-rolling inside the model.

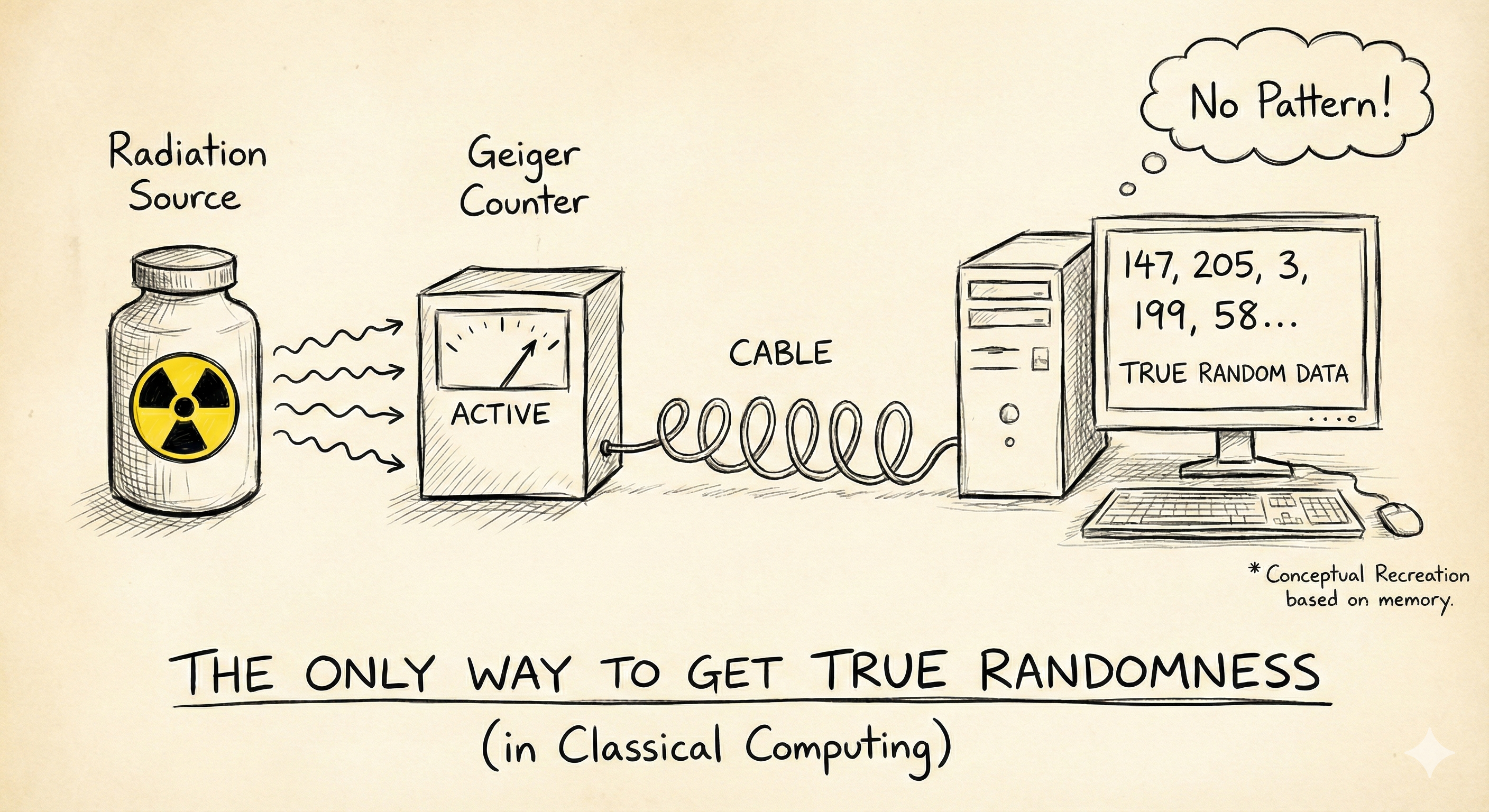

Actually, computers are really bad at providing anything random on their own. I vividly remember a picture that shocked me back in my college days. The chapter started with a drawing of a Geiger counter connected to a computer, and introduced this as “the only way to get real randomness” – a common teaching point at the time. This easily shocked me and made me shoot back “hey, then what are these rand() call results?”. The textbook naturally knew we would ask this question, and kindly introduced the good old reliable way of “pseudo randomness”. Just as we’ve done since the 19th century, we just read from a book of pre-filled numbers. We get a seed (e.g. a page number), visit that page (open this big book), and read the number aloud. Same seed, always the same output. The lesson was: most software randomness is pseudo-random, and true randomness requires a physical source.

We need randomness in many real-life situations. For each, our computer programs use pseudo-randomness to make it work. Even in machine learning, we use pseudo-randomness everywhere. When training a neural network, we initialize weights to slightly different near-zero values (otherwise symmetry isn’t broken and learning stalls), we randomly drop out some neurons during training (so the network doesn’t over-rely on some specific ones and becomes more robust), and we shuffle the training data randomly (so the model sees data in different orders each epoch, making it more robust), and so on. All these are seeded, and can be reproducible in controlled setups.

Sampling of LLMs – How LLMs use (Pseudo-)Randomness

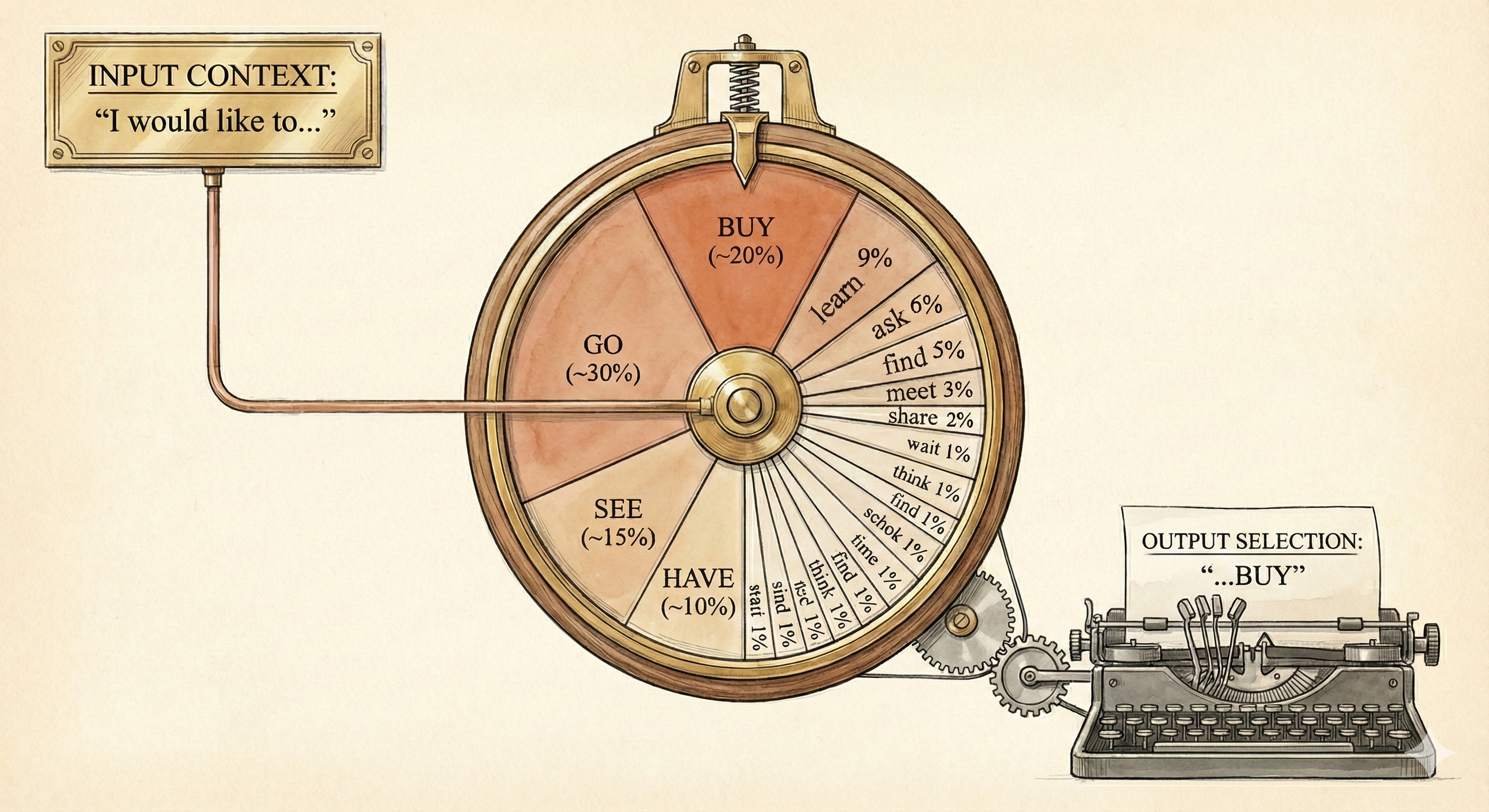

So, how does an LLM actually generate text? LLMs work by predicting the next word, or more precisely, the next “token”. At each step, the model outputs a probability distribution over all possible next tokens. For example, given the prompt ‘I would like to’, the model might assign high probabilities to ‘go’ (30%) and ‘buy’ (20%), moderate probability to ‘see’ (15%), and tiny probabilities to thousands of other tokens. Then, one token gets selected from this distribution. Higher probability tokens are more likely to be picked, but not guaranteed - just like spinning a weighted wheel where some segments are wider than others. This process is aptly called “sampling”.

We can easily see this sampling in action. Let’s say we ask an LLM, “Continue the sentence: I would like to”, multiple times. You will get results like this:

- I would like to spend more time exploring …

- I would like to see more kindness and …

- I would like to have a relaxing weekend …

- I would like to buy a new laptop with …

- …

Each time, the sampling process picks slightly different paths. Each path is valid, each weighted by the model’s learned probabilities. This is what gives LLMs their “creative” feel. The same prompt can lead to genuinely different outputs. The sampling makes the generated sentences much more natural, just as we humans would say – when there is enough content to say, human utterances rarely overlap word-for-word, even when the intention is exactly the same. In a similar manner, the sampling process does land on that ‘long tail’ of tiny probabilities shown in the illustration, leading to different word choices.

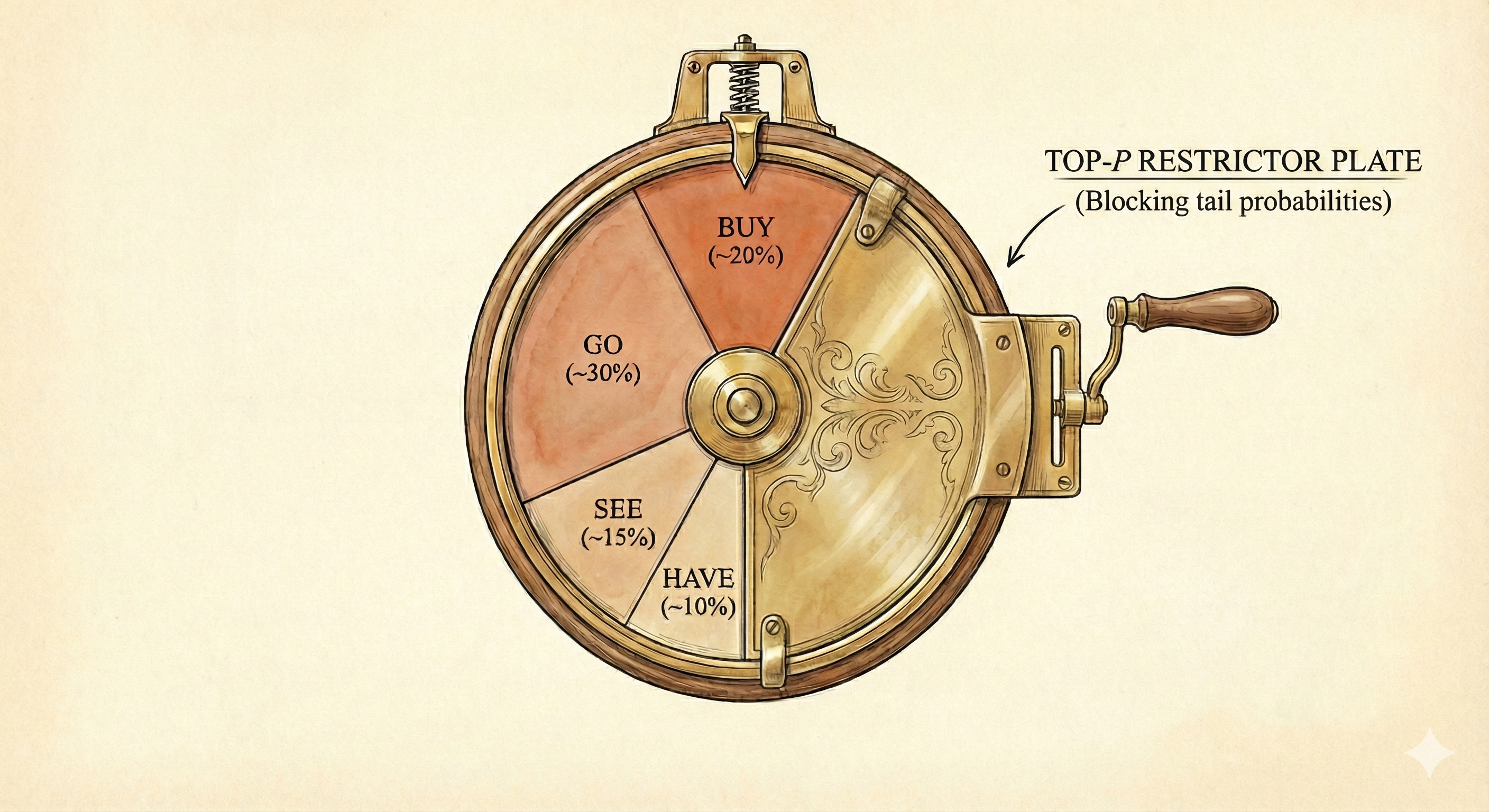

So we have this sampling process that introduces variation. But what if we want less variation? Or more? LLM APIs typically expose parameters to control this. One common parameter is “top-p”. Instead of considering all possible tokens, top-p says: “only sample from the smallest set of tokens whose combined probability exceeds p%.” So top-p=0.75 means: find the most likely tokens that together make up 75% of the probability mass in the given context - then sample from the reduced set. This cuts off the long tail of unlikely tokens (e.g., fewer surprises).

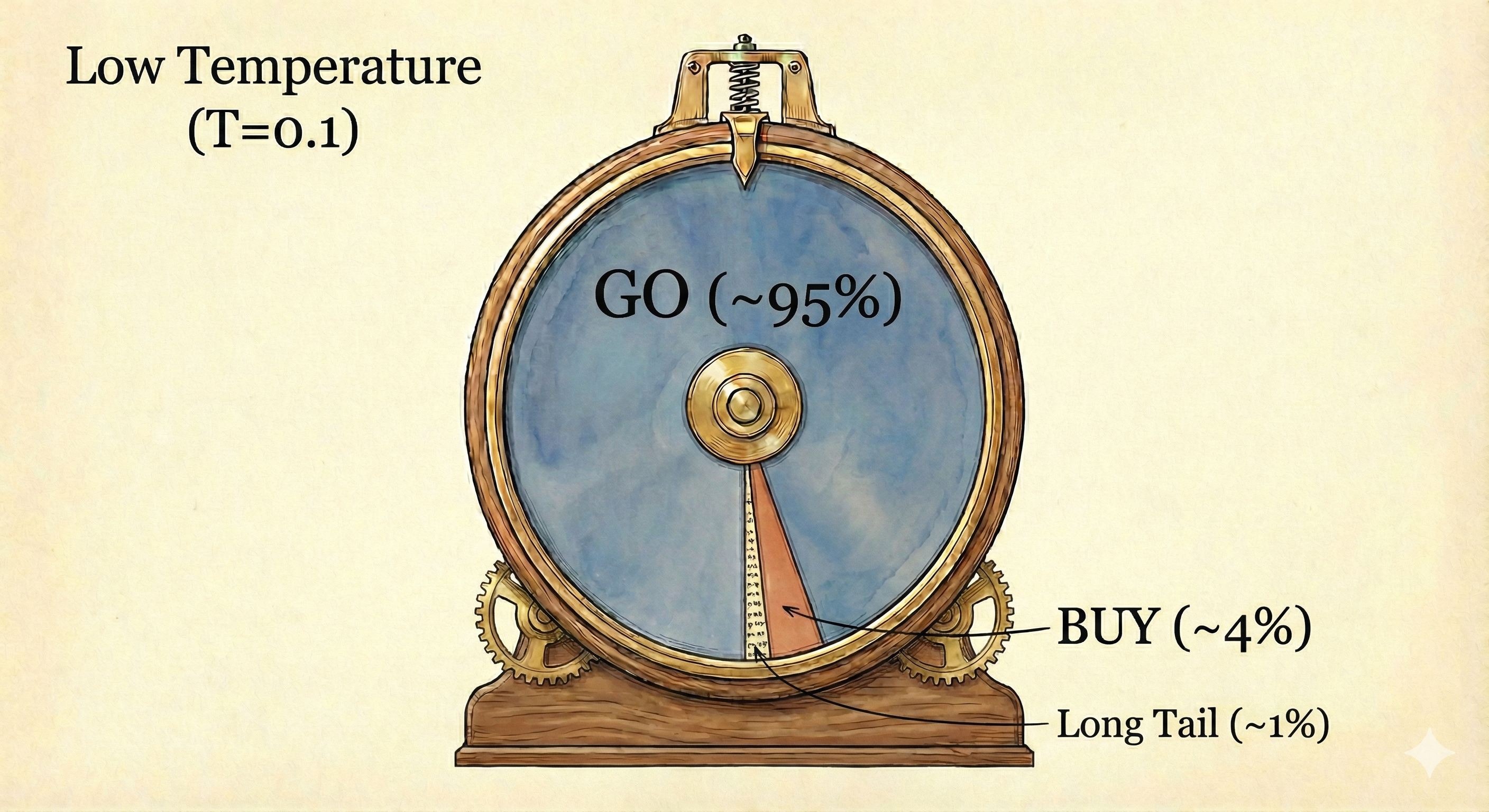

Another common parameter is “temperature”. Think of temperature as controlling how “sharp” or “flat” the probability distribution is. At temperature=1.0, the model uses its original probabilities as-is. Lower the temperature toward 0, and the distribution becomes sharper; high-probability tokens become even more dominant, low-probability ones become negligible. The picture below shows how the original “sampling wheel” changes when we set the temperature to 0.1.

When the temperature is set to 0, sampling effectively disappears: the model always picks the single highest-probability token. This is sometimes called “greedy decoding”. At exactly 0, there’s technically no randomness left - it’s purely deterministic selection. Parameters like temperature and top-p give us some dials – from “creative and varied” (high temperature, high top-p) to “predictable and consistent” (low temperature, low top-p).

But here’s the surprise: even with temperature=0, production LLM models often don’t give reproducible results. Here are some actual call results from GPT-4.1 at temp=0.0.

Input: Continue the sentence. The sentence: The weather was...

On one (unlucky?) day, I got six different variations:

The weather was unexpectedly warm for this time of year, with a gentle breeze carrying the scent of blooming flowers

The weather was unexpectedly warm for early spring, with golden sunlight streaming through the clouds and a gentle breeze carrying the scent of blooming flowers.

...unusually warm for early spring, with sunlight streaming through the windows and a gentle breeze rustling the curtains.

The weather was unusually warm for early spring, with a gentle breeze carrying the scent of blooming flowers through the air.

The weather was unusually warm for early spring, with a gentle breeze carrying the scent of blooming flowers through the air.

The weather was unusually warm for early spring, with golden sunlight streaming through the windows and a gentle breeze rustling the new leaves outside.

So what’s going on here? Why does temp=0 still give us different outputs?

The Hidden Culprit: The Serving Stack

A few days later, I ran the same setup (same prompt, temperature=0, same endpoint) and got only two variations:

The weather was unusually warm for early spring, with a gentle breeze carrying the scent of blooming flowers through the air.

The weather was unusually warm for early spring, with a gentle breeze carrying the scent of blooming flowers through the open windows.

Nothing about my prompt or parameters changed, but the results are different. The likely culprit is the serving stack.

In production, one inference isn’t a single frozen computation. It’s a pipeline of moving parts, and small differences in that pipeline can alter the logits before decoding even starts. Two serving-side ideas matter most for understanding this: batching and Mixture of Experts (MoE).

Batching (why servers group requests)

Neural-network hardware (typically GPUs) is fastest when it runs one big job instead of many tiny ones. That’s why production systems batch multiple requests together: it keeps the GPU busy, reduces overhead per request, and makes inference cheaper and faster overall. If you processed requests strictly one-by-one, the GPU would sit idle between tiny jobs and throughput would collapse.

There are a few batching styles:

- Fixed batching: a fixed batch size is chosen ahead of time. This is common in offline evaluation or when traffic is steady.

- Dynamic batching: the server waits a few milliseconds to gather multiple requests, then runs them together up to some limit. The batch size changes depending on traffic.

- Continuous batching: during decoding (token-by-token), the server keeps adding new requests into the running batch as others finish. This squeezes the most throughput out of the GPU, but the batch composition can change at each step.

For our topic, the key point is simple: in production, your request is almost never alone. It’s grouped with others, and that grouping can vary from run to run under different load. Different batch shapes can also nudge low-level execution paths, which can introduce tiny numeric drift.

Mixture of Experts (MoE): a different way to scale models

Early LLMs were dense, which means every token activates the entire model. Mixture of Experts (MoE) takes a different approach: the model has multiple specialist subnetworks (“experts”), and a router chooses a few experts to handle each token. So each token only uses a fraction of the total parameters. The benefit is scale: you can grow total model capacity and specialization without scaling per-token compute by the same amount.

Many current frontier models publicly use MoE (e.g., Mixtral, DeepSeek, Qwen/Grok/GPT-OSS, and so on). There’s no public proof about GPT architectures, but it’s widely believed to be MoE as well. For our topic, MoE matters because routing decisions can depend on batch load (which experts are “full”), so the execution path (which expert is answering) can shift even when your prompt doesn’t.

Think of it like this: imagine a committee of specialists answering your question, but they’re simultaneously answering 50 other questions from different people. Your question arrives in batch #4791 alongside recipes, tax law, and Python debugging. A certain subset of specialists handles that batch. Run the exact same question again? It might land in batch #4792 with astronomy and medical queries. Different specialists can activate. The output you get is shaped not just by your prompt, but by the invisible computational context it lands in.

Other serving-stack factors

Even if we exclude batching or MoE, there are still small production factors that can nudge results: load balancing across replicas, hardware/quantization differences, and provider-side updates to inference code or safety layers.

None of this is visible from the API, but each can slightly change the internal computation, and that can lead to different outputs even with temp=0.

Let’s revisit the GPT-4.1 weather examples at temp=0. The variations are not necessarily “random” – they are the result of different execution contexts: different batch shapes, possibly different routing, or other invisible serving details. Here’s the practical implication: production LLM APIs handle thousands of requests per second. Your request arrives, gets bundled with whoever else is querying at that millisecond, and processed. You have no control over this computational context, but it can still affect the result.

Reproducibility vs. Efficiency

Now, you might be thinking: “Can’t we just fix this?” And actually, yes — some providers now offer “reproducible” or “deterministic” modes, often with a “seed” parameter. In controlled settings like evaluation benchmarks, this works beautifully: same seed, same input, same output. Perfect for running the same evaluation suite multiple times and getting consistent scores.

But here’s the catch: truly reproducible modes often require fixed batch sizes (sometimes batch=1, processing one request at a time) or dedicated compute instances. This can reduce throughput by 10-100x depending on the system. Suddenly your API calls are slower and/or cost significantly more. So in practice, production systems run with dynamic or continuous batching: faster, cheaper, and accepting non-determinism at the single-inference level.

This is why we can see non-deterministic LLM outputs from production endpoints. Some deployments are stable for certain prompts; others vary; and behavior can shift over time as serving stacks evolve, or loading factors change. Unless you run a local instance with single-batch processing, or pay premium costs for dedicated compute, this is simply how production LLMs often work. The computational context your request lands in shapes the output you receive, and you have no control over it. This is the reality we live in.

Conclusion

So let’s return to our original question: “Does an LLM have fundamental randomness in it?” The answer, as I said at the beginning, is “No, but also Yes.”

No: There’s nothing inherently more random in LLMs than in other programs. Everything is deterministic in principle. Sampling uses pseudo-randomness (our old friend, the book of random numbers). Serving-stack effects are just computational artifacts—different paths through the same deterministic system.

But Yes: In practice, production LLM systems often can’t run deterministically, even with identical inputs and temp=0. The serving stack introduces variance you can’t control: batch shapes and execution paths, routing, replica/hardware differences, and other hidden execution details. Methods exist to reduce this (fixed batches, seed parameters, dedicated instances), but we generally live with inference-level non-determinism in production because the alternative is too expensive and too slow.

… and the Bigger Source of Unpredictability

However, there is more to the feeling that “LLMs seem unpredictable.” The bigger contribution comes from something else: we cannot easily predict how two different but similar inputs will behave. This is what frustrates users and engineers in production. This is more than sampling variance or serving-stack variance. This is emergent behavior from a complex system encountering edge cases in its learned generalizations. The model is trying to solve an inherently underspecified problem – real-world inputs are always ambiguous in subtle ways – and it does so by generalizing from the data it has observed before (training data). Sometimes that generalization is robust. Sometimes it’s brittle. And predicting which is which? That’s the hard part.

Understanding this bigger source of unpredictability – how LLMs generalize, where they fail, and what we can do about it – is the goal of the next article: Part 2.