Call me Gil

Call me “Gil”.

When I say this to English speakers—or indeed to Western language speakers—people sometimes ask me back, “why the middle name?” This is a bit tricky to explain, but Gil is really the way my family used to call me as the “short-form” of my name. This topic is somewhat interesting in how shortening first names differs across cultures. So let me dive in a little bit.

My full name in English is Tae Gil Noh, as written in my passport. When I write my name as an author (like in my papers), I always write it as Tae-Gil Noh, just to make clear that the first name is “Tae Gil” and the family name is “Noh”. When you write this in Korean, my name appears in the opposite order—family name first, then given name: 노(Noh) 태길(TaeGil). So Tae-Gil combined is really the first name. And when you shorten this name, it tends to be the last syllable, 길(Gil).

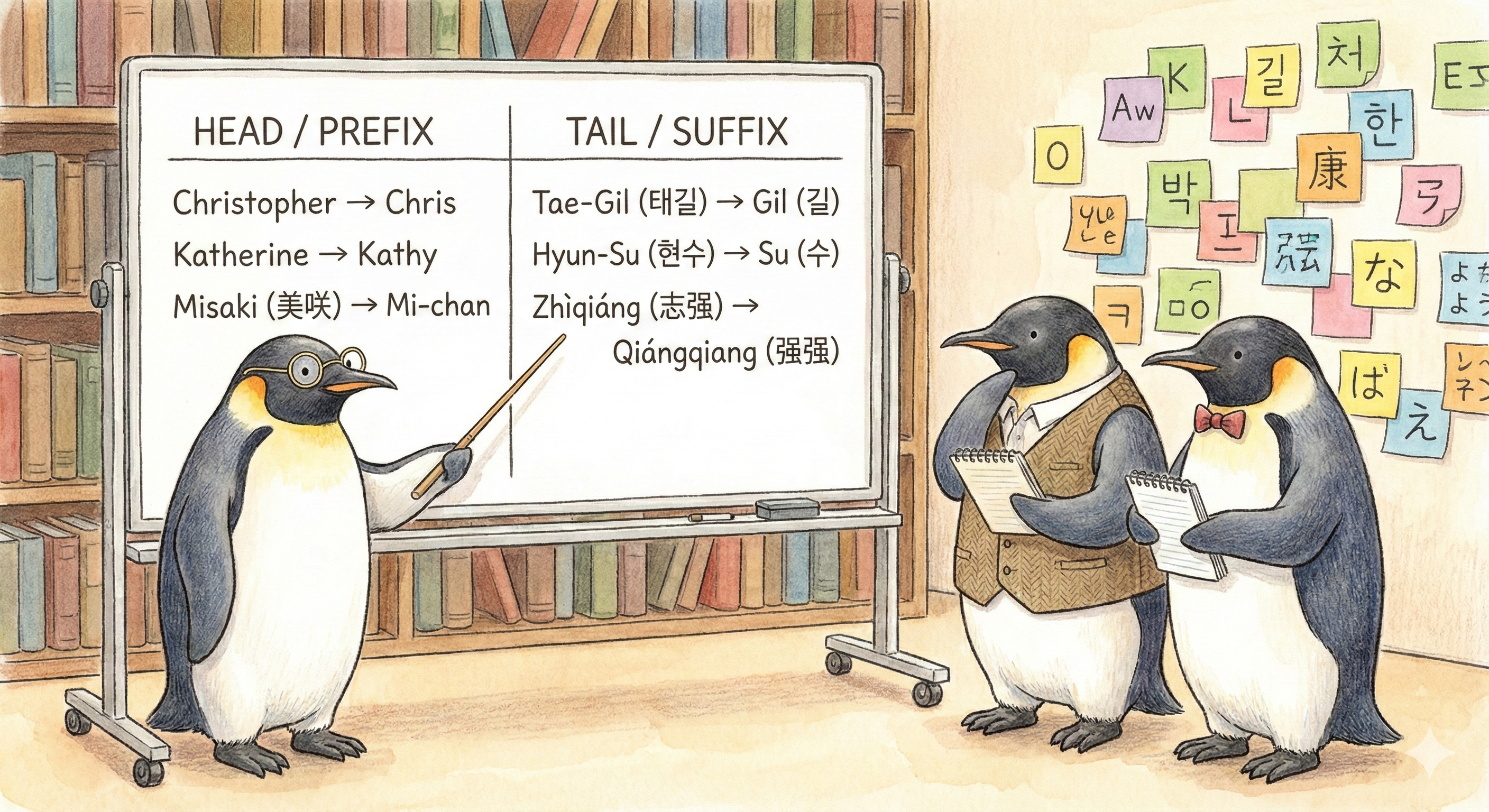

Normally for English names, the head part remains and the tail part is reduced—such as Chris for Christopher, Kathy for Katherine, and so on. There are exceptions like Becky for Rebecca, but head-part remaining is more typical. German seems to have more variants (often with lots of “i”s: Michi, Basti, Matti…), but it’s kind of similar to English.

But in Korean, when you shorten a first name, the general trend is the opposite. You often use the tail part as the nickname. In East Asia, first names mostly have meanings and tend to be noun phrases—such as noun-noun, adjective-noun, or adjective-adjective (adj-adj as a noun phrase with ellipsis). Korean names typically have two syllables, as do most Chinese and Japanese names. For example, my name is written in traditional Chinese as 泰吉, which means roughly “greatly auspicious (omen)”, or “very good (sign)”. It’s an adjective-adjective form. The meaning remains with “Gil” (auspicious/good), but not so much with “Tae” (very/greatly). Korean names like Hyun-su (현수), Ji-Won (지원), Seong-Min (성민) will generally be shortened with the last syllables—such as “수야” (roughly “hey Su”), “원아” (“hey Won”), “민이야” (“hey Min”).

Although, being the head part of the phrase is probably not the main reason it’s selected in short forms. Japanese names and Chinese names are also composed mostly as noun phrases out of Chinese characters, but their “shortening” rules are different. For Japanese, first syllables are mostly selected for making diminutive or endearment forms. Misaki (美咲 - beautiful blooming) is called Mi-chan, and Daisuke (大輔 - great helper) is called Dai-chan. On the contrary, Chinese is closer to Korean nickname-making. They tend to prefer the second/last syllable and use it for pet names. You can call that syllable twice, such as Zhìqiáng (志强) becoming Qiángqiang (强强 - repetition of the second syllable). Or sometimes add an adjective to that syllable, such as Xiǎo Qiáng (小强 - adding a syllable with the meaning of “small”), or sometimes adding “Ā” (阿) as Ā Qiáng (阿强).

So it really depends on the language and its users—even between similarly “generated” names of East Asian languages.

Various causes have been identified for cross-linguistic differences in nickname/hypocoristic formation, including phonological constraints, pragmatic functions, morphological productivity, and cultural attitude shifts.1 It seems that this still remains an area of linguistic research, and naturally there is no universal, easy method of name truncation that applies across all languages.

So this is the story of why it is Gil out of “Tae Gil Noh”.

Hey there, nice to meet you. Please call me Gil.

-

Book: Diminutives across Languages, Theoretical Frameworks and Linguistic Domains (typically accessible via university library access) ↩